pub607-23

Lecture 2: Digital Text Production

Let’s build up a conceptual model of digital text production, from the ground up.

We will proceed in four ‘movements’ – with some breaks in between.

Movement 1. Alphabets, ASCII, and Unicode

“In the beginning was the Word”

…but it’s all just ones and zeros, right?

A ‘Word’ = a Byte. 8 bits.

How do we make bytes into something useful, like text? It’s just a convention. There needed to be – across all computer systems makers – a general agreement that a particular number, represented as a byte (in 8-bits,a number between 0 and 255, between 0 and 1111111, or more conveniently, in hex, between 0 and FF), stands for a particular letter of the alphabet.

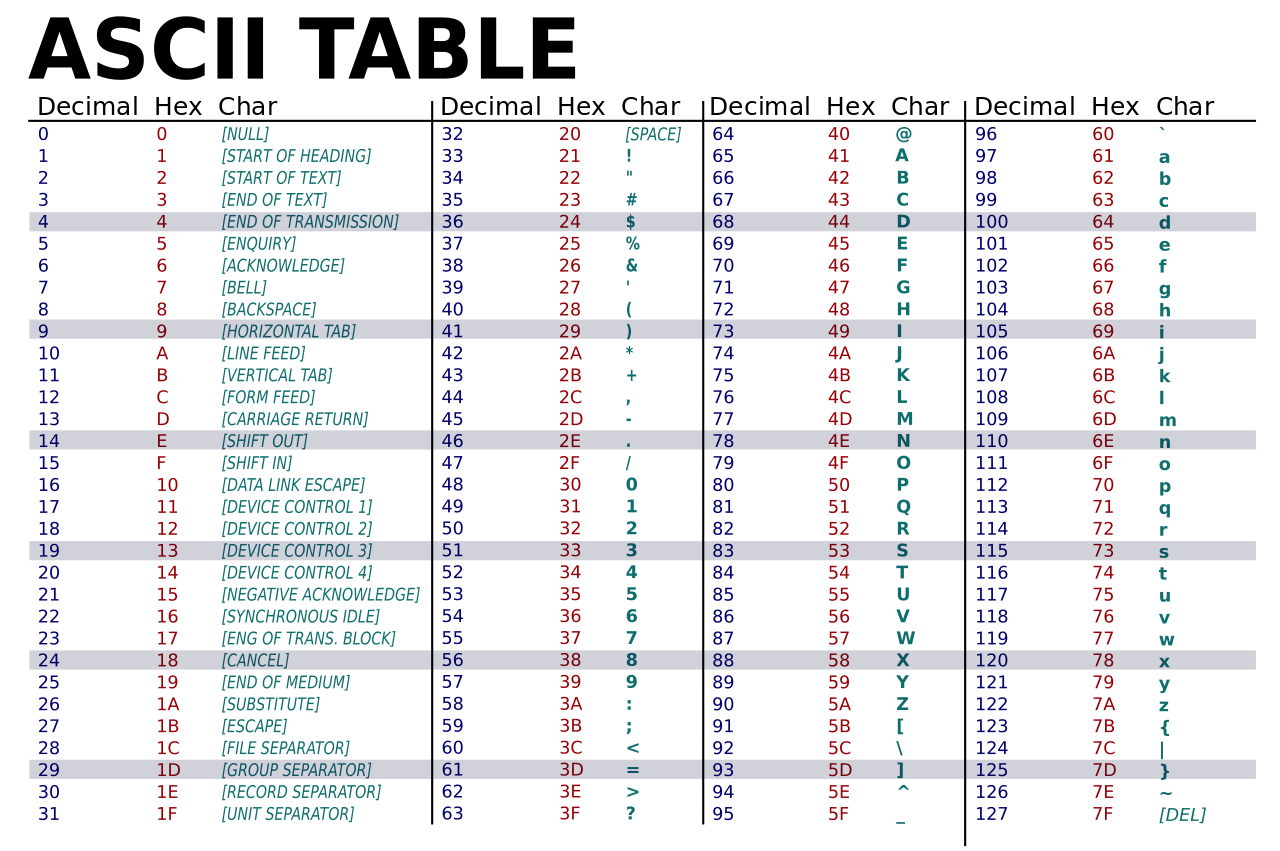

ASCII – the “American Standard Code for Information Interchange” was an enormously successful standard – still with us today, after 60 years (1963).

Capital ‘A’ is ASCII code 65 – or 41 in hex (right?) – ‘B’ is 66, and so on.

How many letters in the English alphabet? 26

x2 for upper and lowercase - 52

- ten digits - 62

- 30 punctuation marks - 92

- 30-odd control codes for early systems - 127

- the last binary bit reserved for error control - 255

So ASCII is an alphabet with 127 possible characters. Sounds great, what could possibly go wrong?

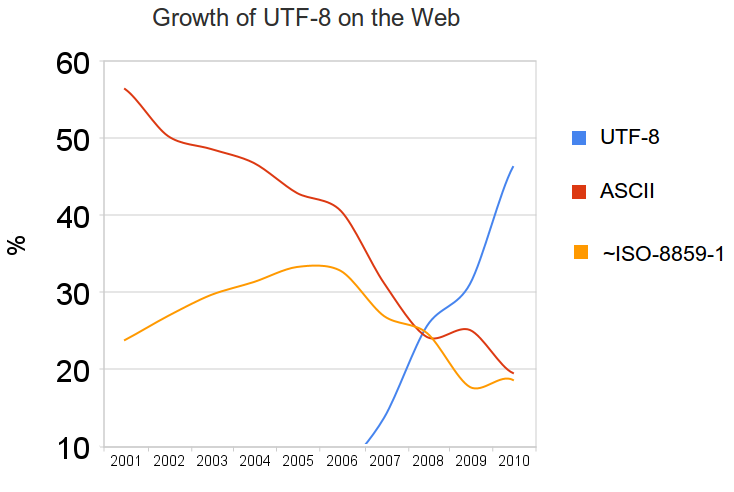

To get around the anglocentrism of that, a variety NON-standard schemes emerged. “Eight-bit extended character sets.” Apple had one, Microsoft had a different one. IBM had another. Various standards were proposed (e.g., ISO 8859) but not uniformly adopted.

But a mess, generally. And non-Europeans (e.g. China) were still utterly left out.

Unicode

A solution came forward circa 1997, in the Unicode standard, which could encode a possible 1,112,064 possible characters

The simplest Unicode implementation, UTF-8, made for an easy replacement for ASCII. Based on fixed 8-bit chunks (up to 4 chunks, for a million characters), and “a UTF-8 file that contains only ASCII characters is identical to an ASCII file.”

But implementations are still complex. This is literally like changing the alphabet from under us.

Unicode is supported by pretty much everything now. Mac OS X, Windows, Unix and Unix-derived operating systems. XML, HTML, and the Web and Internet standards.

But legacy systems are still with us. Old software (esp critical databases) sometimes don’t get updated, and so stuff still messes up.

If you see little rectangles, or these things – �  ⸻ – something in your toolchain has failed to support your Unicode.

The failures are few and far between these days. SoUnicode support means is that you can type accented characters, and curly quotes, and em-dashes, and greek, and whatever without having to worry about it. But this is recent – only the past 10 or 15 years.

You used to have to write U+2014 or — or — but with Unicode, you can just type an em-dash. On the Mac, shift-option-hyphen.

And, of course, you can also write in Arabic or Bengali, or whatever.

Important piece of trivia about Unicode:

A “code-point” is not a glyph. A code-point is an abstract representation of a character in the system. A glyph is an actual mark. So, individual glyphs – for instance, ligatures – are variable, and are actually defined in individual fonts.

In all the fonts in the world, there are only a tiny handful that represent all of the Unicode space.

Pay attention to what Unicode support your typefaces include. Old fonts are sometimes terrible.

If you’re working with an Indigenous language, for instance…

Line breaks

Once we have an alphabet we can all agree on, we can put text in files.

The original, most basic structural element in text files is the line break. Also known as “carriage return”. Unfortunately, in ASCII (and Unicode), there are two of them: line feed (LF, from teletype) and carriage return (CR, from typewriters) are represented. And if there are two ways to do things, people will do both. Or either. And so, historically, some systems used LF, some CR, and some, unfortunately (Microsoft we are looking at you), BOTH.

It’s not a huge hassle, but something to be aware of. For the most part, it just works, because most software is smart enough to do the right thing with whatever version of line breaks are present.

The old Unix practice for text files was regular line breaks (LF) making lines about 80 characters long. Early text editor software edited one line at a time. So the line was the fundamental unit of structure in a text file.

Later, after decent display technology came along, and the “word wrap” feature became normal, people stopped breaking lines at the 80-character mark, and instead could allow lines go as long as they need to be. So today, in a text file, an entire paragraph would be one “line” even though, when you look at it on screen, it’s wrapped into several visual lines.

You’re probably so used to this, that it takes a minute to think about what this means: “Lines” are sequences of text separated by line breaks. What you see on your screen as a line, though, may be a single long line “soft-wrapped” so that it fits within the margins or the window. Almost all software has decent paragraph-wrapping algorithms in it. Some are very sophisticated, like typesetting routines that can hyphenate and control for widows and orphans. Some are simple, and just wrap lines between words when needed.

Movement 2. Understanding Markup

Beyond lines, any attempts to put more structure into text files requires the use of some kind of special delimiter to make it possible to distinguish between regular content and information about the content.

“Markup” is a very old idea. As far back as the 15th century, for instance, the copy that was handed to a typesetter or compositor would be the “fair copy” of the text plus some extra markings that indicated formatting: make the title centred on the page; set this part in a bigger face; break the page here; indent this part; and so on. The standard set of “copyeditor’s marks” are derived from this tradition.

When computers began to be used in typesetting in the 1960s and 1970s, a whole host of systems were invented to embed typesetting machine instructions (that is, programming code) in the text to be set. There are a LOT of different ways of doing this – often using punctuation in weird ways.

Embedding typesetting code directly into an article or book chapter is a tricky thing to do. First, if the instructions get mixed up with the text itself, you will have a mess. Second, instructions to a typesetting machine are complicated and ugly.

In the 1970s, there emerged a practice known as “generic markup” in which the embedded typesetting instruction wasn’t raw code, but rather a label, like “title” or “indented-quote” or something like that. A bit of processing software would then read the file and translate those generic labels to the raw typesetting code.

This had a couple of advantages. First, it allowed editors to be the people who could embed the markup, as opposed to programmers. But also, copy marked up “generically” for one typesetting machine could be switched to a different machine or system just by changing the processing code, as opposed to having to re-prepare the text itself – because it only had generic labels embedded. T

The outcome of this line of thinking, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, was called Generalized Markup Language (GML), which was then certified as an ISO standard in 1986: Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML).

In SGML there are a small set of basic rules:

-

Markup is kept in plain text files;

-

Markup tags are delimited by < and > characters;

-

Markup tags identify the semantic structures of the text, not formatting instructions; formatting is handled separately;

-

The ‘vocabulary’ of possible tags is domain-specific. You can make up a markup language for any context or situation;

-

Markup tags (almost) always come in pairs, surrounding the text that is being identified;

-

Markup tags form a nested hierarchy of structures in the text; a text is thus a tree-shaped information structure; an “ordered hierarchy of content objects”;

-

This hierarchy is readable by a piece of software called a parser; furthermore, rules specifying which tags can be used, and in which order and combinations. These rules can be checked by a piece of software called a validating parser. (one of the key designers of SGML was a lawyer)

Between 1986 and the late 1990s, the primary users of SGML were the American defense department contractors – the makers of planes and bombs and tanks and things. This is because the Pentagon made SGML a documentation requirement for all contractors – for the same of interoperability and longevity (avoiding lock-in).

The goal of interoperability, or conversely, avoiding lock-in or forced dependence on a particular vendor or platform, requires first an open file format, as opposed to a file format whose internal structure is only known or fully understood to the vendor. The original SGML specification made this explicit, by basing SGML files on text files.

Evolving Markup

In 1990 Tim Berners-Lee used SGML to create the markup language for his brand new “World-Wide Web” project. HTML (HyperText Markup Language) defines web pages, and allows them to be interlinked. HTML is a very simple application of SGML, but within a year or two of its launch, the number of people using HTML outnumbered the defence contractors using other kinds of SGML. The idea had broken out of its industry coterie beginnings and into mass consumption. And while the original HTML standard was pretty sketchy, considering that it was headed for world domination, it actually worked pretty well.

In 1997, a committee drew up a design for a “version 2.0” of SGML, written with the Internet in mind. It was a bit simpler, more streamlined, and did away with the need for validation (there weren’t any lawyers on the committee). They might have called it SGML 2.0, but instead they thought it would sound better if they called it XML, because X is the sexiest of all letters, right?

XML was the successor to SGML for the Internet era, especially for the industrial applications in which SGML originally succeeded. But although HTML it has taken a tortured path over the past thirty years, the HTML that makes up the Web has, in practice been by far the most dominant stream of XML development. Purists and pedants will argue that HTML isn’t really XML. But they are purists and pedants. It is too.

In practice, the XML specification defines only how the tags are written; it doesn’t specify what the tags are. That part can be “domain-specific,” which means that there are many XML languages, each of which is designed to do a particular kind of work.

Let’s look at some examples of XML

Movement 3. Markup and Formatting?

From the very beginning, accessibility was an explicit goal of SGML (see, for instance, https://www.w3.org/2000/10/DIAWorkshop/accesssep.html). Because the markup defines the semantic structures of the text only, and keeps formatting processes separate and secondary, it is possible to have a single source – an XML document – that produces typeset print, braille, and mobile-phone versions by specifying different processing for the same source text.

XML only tells us is what is in the text – the content and its structures and parts – but we can use those structures as hooks for formatting rules.

For most reading contexts, a stylesheet defines formatting rules for named structures in the text. Conceptually, this works the same in Microsoft Word, in Adobe InDesign, in your web page, and in XML more generally.

We define rules that say things like: body copy should be 10pt Garamond on 14pt line spacing, with a 56 em line length. First-level heads should be 18pt Gill Sans – unless they appear in the context of a sidebar, in which case it should be 12pt instead.

A stylesheet like this produces a “templated” design – as opposed to being hand-crafted or bespoke. The power of a templated design is that the same stylesheet can be applied to many documents. It also means that one stylesheet can be swapped for another – changing the formatting of a document without changing the text itself. Such an approach may be useful in the context of accessibility, or in multi-mode delivery.

This formal separation of the text (and its named structures) and the formatting rules is one example of the concept of “separation of concerns,” which is a more general design pattern. We have had separation of concerns in publishing since Gutenberg put moveable type into practice, and the abstract idea of a text – in the form of a marked up manuscript that compositors would use in typesetting – came to drive formatting.

This separation of the platonic ideal of the text from any particular printed instance of it has both delighted and vexed scholars and critics ever since. At this very point, when the text becomes abstract and mutable, it also becomes capable of fixity and durability over centuries owing to its production and distribution in mass quantities. It is also capable of much more.

Ironically, the Desktop Publishing tradition, embodied today in InDesign, runs counter to this idea… in InDesign, format is structure, not the other way around. If in the DTP model, we begin foundationally with what the text looks like, in terms of page layout and formatting, then it is a harder path to extracting the text for use in a different context – like in an ebook; or in a screen reader; or for some other purpose altogether.

HTML & CSS

HTML, as mentioned earlier, had a bit of a bumpy start. One problem was that for the first whole decade of the Web, there was no separate formatting system in place, and so all the formatting on the early web was done by hacking the HTML itself in terrible ways.

One commonplace was to achieve layouts by padding layouts with “invisible pixels” – a 1-pixel by 1-pixel .gif file that was inserted and then stretched (in the HTML) to whatever dimensions were required for the layout. Another horrible idea was the use of tables with invisible borders to achieve layouts. And ubiquitous was typographic specifications written right into the HTML.

This eventually got solved with Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), which web browsers began to support around the turn of the century. CSS gave designers a separate system to define layout, typography, and even some interactivity, leaving the HTML to do what it was designed to do: define the structural components of the text.

What really made this system work was the rise of blogging and other content-management systems (e.g., Wordpress), where publication-level details like layout, typography, and “themes” were kept in the back end, and authors were encouraged to concern themselves with the text alone. After Wordpress, HTML on the web got cleaner and more standardized, making it more like what XML was supposed to be.

Today, lots and lots of systems beyond websites are built using HTML. EBook standards – both the consortium-backed EPUB format and most (but not all) Amazon Kindle file formats have HTML inside, representing the content itself. Loads of technical documentation systems, online help systems, and so on all use HTML as a basic system. There is a significant trend to building scholarly journals in HTML, as opposed to a more complex and specialized XML tagset. Even a few trade publishers – Hachette in particular – have HTML at the core of their book production workflows.

HTML has emerged as a general-purpose prose markup language. There are other MLs for specific industrial and scientific applications, but probably at least 90% of the time, HTML will do the trick.

(It’s worth noting here that modern web applications use HTML, and CSS, and also a third layer provided by Javascript. Javascript is a programming language that can run in your web browser and do things with your content, including providing user-interface niceties. Javascript is outside the scope of this course; it has only limited use in ebook production because many of the things that use it on the web create security holes for ebook systems and vendors.)

Movement 4. Markdown

The trouble with HTML is that it’s ugly and probably unnecessarily verbose. Looking at it raw, one would never want to write or edit in HTML directly. It always will require some kind of editing tool to provide a friendly interface. Some of those interfaces will even pretend to be “WYSIWYG” even though this is an oxymoron in the context of markup.

An alternative approach was developed in the 2004 by blogging pioneers John Gruber and Aaron Swartz. Markdown was a way of writing on plain text files with an extremely minimalist set of extra formatting cues added – that could then be automatically converted to HTML. They called it markdown (it’s a joke) and released it online.

You’re looking at it.

Markdown, while visually minimal, is explicit and complete enough to be unambiguously transformed into HTML by a simple software routine. That means that markdown is an alternative form of markup that does that same work as HTML, but it doesn’t look like HTML or XML at all.

Markdown caught on in the years since 2004, and became embedded in lots of different web publishing systems. A host of software tools were developed to support it, and to allow writing, editing, previewing, converting, and so on.

For most intents and purposes, markdown can be used anywhere that HTML is needed, because it’s trivially easy to convert between the two. Markdown removes the need for a pseudo-WYSIWYG editing interface. But much more importantly it keeps close to the key advantage of text files in the first place: you are looking at the content, and the file, and they are the same thing; there’s no extra interpretation going on, in between you and the file itself. There is no mystery. We might call this “WYSIATITI”: What you see is all there is; that’s it.” Maybe, in honour of Madeline, “That’s all there is; there isn’t any more.”

Markdown is useful for writing, but it is supremely good for editing, as I have found in the decade or so I’ve been using it. That’s because it’s so simple and clean; there’s no extra noise in a markdown file, and so it’s easy to edit and process. The work you do in PUB607 should bring this home for you.

Pandoc

One of the key pieces of software we will use with markdown is Pandoc – which bills itself as the “universal document converter.” https://pandoc.org

Pandoc is a simple, open-source tool that can take pretty much any structured content (or even semi-structured, with caveats), parse it, and re-create it in any other structured format. It was originally designed as a markdown-to-HTML conversion tool, but it has been generalized to work with dozens of different input and output formats.

What that means is that it takes any structured (or even semi-structured) document format, and parses it into an internal representation. That internal representation can then be re-written in any other structured document format.

Pandoc is extremely high-quality software, and it is exquisitely well documented. I have often said that “a close reading of the Pandoc user manual would constitute a whole course in document production.” Since you’re currently taking a course in ebook production, it would be a good idea to at least familiarize yourself with Pandoc’s incredibly well-written User’s Manual: https://pandoc.org/MANUAL.html

Pandoc, it must be said, has a command-line interface. That means you use it by typing commands into a command shell, like it’s 1983 all over again. You have one of these, though: on your Mac, it’s called “Terminal.” On Windows, it’s called “Powershell.”

I know, it’s old, and it makes you feel like you’re in an 80s movie. But the command-line interface actually really works incredibly well, especially for text processing, because it was invented for text processing. If you want to be one of the cool kids, you’ll play with the preferences in your shell so that it’s green type on a black background. Embrace your inner geek!

Here’s a Command-shell cheat sheet

Pandoc isn’t hard to use, once you get the general idea of how it works. Here’s a Pandoc Tutorial